Rennie went into the church to get out of the sun. Her face was burning. She’d gone to the supermarket to buy the weekly groceries for her mother and herself.

The church was blessedly cool. The darkness made it hard to see at first and her eyes took a few seconds to adjust. Then she slid into a seat near the statue of the Virgin Mary and put her groceries at her feet. She rested her hot forehead on her arms.

After a while Rennie felt better so she raised her head to look around. The church was old by Florida standards. It was made of wood and had wooden benches instead of the orange plastic chairs Rennie had seen in other places. The floor was wooden, too, and the church had escaped the worst of modern decoration. The statues were garishly painted, though. The Virgin Mary looked like she had on a bit too much makeup, and the baby Jesus, suspended dramatically above the nave, was bright pink from head to toe.

Rennie liked the statue of Saint Francis the best. At least she thought it was him. Her religious instruction, like the rest of her education, was sketchy. The statue showed a man holding an eagle, and Rennie vaguely remembered Saint Francis protecting the animals. The statue’s face reminded her of her father’s. He’d had a reddish beard and piercing green eyes, too. She noticed candles burning at the feet of all the statues and she went to have a look.

A card pinned to the wall read, Big Candles 50 cents. Little candles 25 cents. Bless You and Have a Good Day. It was a plain, white card. Nothing like her mother’s new business cards. Her mother worked in a beauty salon in Palm Beach. Her business card, printed on shiny, pink cardboard, read, Marilyn’s Marvelous Manicures.

“Rennie, your classes in that junior college are taking you nowhere. What are you learning there? I think you should enroll in beauty school,” her mother had told her last week. “We could set up a business together. We could call it ‘Marilyn and Renée’s Beauty Shoppe’.”

Rennie’s real name was Renée, but no one called her that.

As she thought about the future, tears welled up in her eyes. She blinked once and they rolled down her cheeks. The bright Florida sun would bleach all her dreams right out of her. Her dreams of leaving the state, of going to a bigger university and getting a degree. Her dream of having a house with a real garden. And even the simplest dream of finding a job she’d like, not doing manicures with her mother or sticking curlers in some lady’s blue hair. If only she had an idea of what to do with her life.

She looked up at the brightly painted statue and found her lips moving. “Help me, Saint Francis. Please. Help me get out of here. I don’t want to be a beautician.” The tears ran down her face faster and faster. “I don’t want to be part of my mother’s life forever.” At these words, she felt cruel. That made her cry even harder.

Rennie stood stiffly, resolved to try to become a better person. She sniffed one last time and turned to the door. Her eyes were so blurred with tears she almost bumped into someone on the way out. Slowly, she started walking homeward.

“I will not daydream anymore,” she told herself firmly. “I will work hard to earn more money. I will help my mother. I will think about beauty school.”

She wiped her face. The heat of the sun dried her tears in seconds, leaving silvery, salty traces on her cheeks. She sighed and straightened her shoulders. “Only ten more blocks, just ten more blocks,” she said.

* * * *

On his way to the tack shop, Juan saw a little wooden church standing by itself under two fig trees. His mother had been devout, he’d gone to Catholic school and his family went to church regularly. Although he hadn’t gone to mass once since coming to Florida, he swerved his car into the parking lot and went into the church on a whim. After last night with the French brothers, Juan had realized how much he missed his mother and brother—he would light candles for them.

The darkness blinded him for a moment. Then he saw the girl. She was kneeling in front of a statue he recognized as Saint John from the eagle, and she was crying.

Her hair was the first thing he noticed about her—the color of sun-kissed apricots. It hung in a neat braid halfway down her slim back. She was dressed in cut-off denim shorts and a pale orange T-shirt that looked as if it had started out another color before being in a disastrous wash. Her feet were shod in plastic flip-flops, also orange, and faded.

When she turned around his breath caught in his throat. She looked like the Madonna his mother had hanging over her bed. The painting was old, Flemish, and the girl, by modern standards, was not beautiful. Her face was too round on the top and her chin too pointed. Her brow was high and pale. Her eyebrows were pale, too, like her hair, and her mouth was not the large, full mouth that was in fashion. It was small and folded like a flower. Like the Madonna in the painting, she had immense gray eyes as clear as rainwater. They were full of tears now, and red-rimmed, but her lashes were thick and dark. When she stood, he noticed she was tall and thin. Her arms were tan and pale freckles dotted her nose.

As if in a daze, she walked right past him out of the church and into the blinding sun. She smelled like fresh-cut grass and her hair caught the light when she walked outside and flashed red-gold. Then she was gone.

Juan sighed and walked to the statue of the Virgin. He lit two candles and said a prayer for his mother and brother. He tried to think of Rosa, too, but his thoughts kept straying to the slender redhead who’d been kneeling in the church. Why had she been kneeling in front of the statue of Saint John? He loved Saint John’s the best of all the Gospels, but it was the most complex. He wondered at the significance the girl accorded to him.

Then his eyes were drawn to three large bags of groceries sitting under the bench. They were rather squashed, as if they’d been shoved there out of the way. He thought they must be the girl’s so he picked them up and went to his car. He would try to find her.

In the end, she was easy to find. Her hair shone like a beacon from way down the dusty road. She’d taken the second left-hand turn and was walking along the broken sidewalk with her shoes going clip-clap against her feet. She didn’t walk so much as she floated. She stood straight, her thin shoulders pulled back by invisible wires, her head held high. She had long legs, tan and smooth.

He slowed his car down to match her pace and leaned out the window to call to her. “Miss! Miss!”

She glanced over to him but kept walking. He thought she looked nervous.

“Did you leave your shopping in the church?” he called.

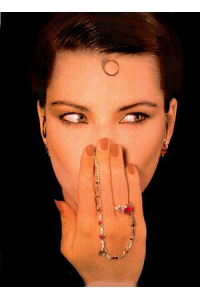

At that, she stopped, a horrified expression on her face. She clapped a hand to her mouth. “Oh, no!” she wailed.

“Don’t worry. I have them right here in the car.”

She glanced to the left for traffic then dashed across the road. “Thank you so much!” she said warmly. “I really appreciate you coming after me. That’s so nice.”

She smiled and her teeth were white and even. Even her voice was delightful. Her hands were long and thin, like the rest of her. However, when she leaned up to the car window, he saw that her breasts were beautifully rounded, full and strained against the flimsy T-shirt. A wave of heat rushed through him. It was a strange feeling that encompassed her breasts, her scent and the color of her eyes.

“Do you live far? I’ll give you a lift if you wish.”

“Well…” She hesitated for a minute then smiled, getting into the car. “All right, it’s not too far. Take the next road to your right, at the light. I live next to a chicken restaurant, you can’t miss it.” She giggled and the warm sound tickled his ears.

“My name’s Juan,” he said. “What’s yours?”

“Renée.”

“It’s French,” he said.

She looked surprised. “Yes, but everyone calls me Rennie. Actually, if you called me Renée I wouldn’t realize you were talking to me. Only my father called me that.”

Juan caught a trace of sadness in her voice as she said that, but didn’t comment. Last night’s conversation with the French players had reminded him just how painful the past could be, even when brought up with the friendliest intentions. “Is that the turn?” he asked, seeing a large sign with a red hen on it. The hen was dressed like a farmer holding a basket of eggs under her wing. The sign said Den’s Fryers, and something about going Cuckoo. Juan thought he’d probably go loco if he had to look at that sign all day. He’d been brought up in a household where good taste was considered very important.

“Yes, thanks. Why don’t you come in and have something cold to drink? It’s awfully hot out,” Rennie said as she gathered up her groceries. “I have iced tea in the fridge.”

“Here, let me get those,” said Juan, taking the bags from her.

Rennie looked surprised. “Thanks.”

Juan followed Rennie up the steps on the outside of an old wooden house. It was built colonial style and had once been a large, single family home. Time had divided the house into flats and faded the paint and woodwork so that hardly a trace of the old mansion could be seen. All the doors were painted different colors now. Rennie’s door was pink, he noticed. There was a pot of white geraniums near the door, with a bowl of cat food shoved behind it.

The apartment was cool—closed shutters kept the sun out. Potted plants abounded, some on the floor, some on tables, and the furniture was mostly wicker, with cushions in a light floral pattern. No paintings or posters hung on the walls, but there was a huge bookcase stuffed with books. Books overflowed onto the floor and were stacked neatly according to size. In a round bowl placed on a table, a goldfish swam in lazy circles.

Rennie put the groceries on the counter that separated the tiny kitchen from the living room and motioned Juan toward a chair.

“Have a seat,” she said. “I’ll just be a minute putting these away. What would you prefer, a soda or iced tea?”

“I’ll have the tea,” he answered. He sat in the chair next to the goldfish. The floor was bare, pine boards in the living room, linoleum in the kitchen. Everything was spotless. The apartment smelled nice, like flowers. There wasn’t the smell of old tobacco. No smokers here, he decided.

He watched Rennie. Her movements were quick and decisive. Her hair was coming loose and tendrils hung around her face. Botticelli’s Venus came to his mind—Rennie had the same grave look. She caught him staring at her and blushed.

“I look awful,” she apologized. “It’s this T-shirt, it’s so old. I was just going shopping and, well…didn’t think I’d be meeting anyone.” She shrugged. “Here’s your drink. Are you Cuban? I noticed your accent.”

“No, I’m from Argentina.”

“Wow! That’s far away. Is it nice there?” she switched to Spanish and spoke with hardly an accent.

He grinned. “Where did you learn to speak Spanish?”

“In school, where else? Here in Florida we’re mostly hearing two languages now. It’s all over the radio and TV. I think it’s great. I wish I could learn more languages. I’m taking French classes in college, but I’m not getting very far. Is Argentina nice? Are you here on vacation?” She settled on the sofa facing him, then she blushed. “Sorry, I talk too much.”

“Argentina is wonderful.”

Juan found himself telling her all about his life on the farm, and about his family. He spoke about his mother, about his father moving to England and leaving him and his two older brothers in Argentina. He talked about polo and the problems he was having with his boss.

Through it all Rennie listened with wide eyes. Clearly, she was fascinated.

Juan couldn’t remember feeling so much at ease with a person, or being able to talk so freely about his family. Even with his fiancée, Rosa, there was that frown of censorship that marred her face when he mentioned his father. She thought he was a criminal to run away to England after his wife’s death. Rosa only wanted to talk about marriage and children and how Juan would run the farm when they were married.

Rennie was especially interested in polo, and laughed when he came to the part about Andre’s groom running away.

“He found someone right away, didn’t he?” she asked.

“Nope, I saw him this morning riding his horses out on exercise and mucking out the stalls.”

Rennie looked thoughtful. “I wish I could be a groom,” she said. “I can ride and take care of a horse. Is the pay any good?”

When he told her, she gave a shriek. “Oh, please, please let me try! Introduce me to Andre, I’ll work for half that, I’ll learn quickly, you’ll see, and work hard. Please, please? I promise I won’t get pregnant and run away!”

“Are you serious?” he asked. His heart gave a strange flutter as he watched her face light up. Suddenly, the most important thing in the world seemed to be to make this serious, gray-eyed girl smile.

“Yes, a thousand times yes!” Rennie cried. “Just give me a chance. I know I can do it.”

Juan nodded. “Okay, I’ll let you try. You’ll be on a trial basis for one week, and if all goes well, we’ll hire you for the rest of the season until mid-April. But I don’t decide. It’s Andre’s decision. All right?”

“Okay.” She frowned. “What do I have to wear? Hardhat and breeches?”

“No, hardhats are only mandatory in England, although I think they’re a good idea. Just any working clothes. You’re going to get dirty. Can you come to the stables now?” he asked, checking his watch. “It’s three-thirty, Andre should be there.”

“Hold on a sec, I’ll change.”

She ran out of the room and he could hear her through the paper-thin walls digging around her closet for clothes. Soon she came back wearing jeans and a new T-shirt. Her hair was brushed and braided tightly and she wore low riding boots that looked old, in spite of the polish that made them shine.

She caught the direction of his glance and laughed self-consciously. “Aren’t they sweet? They were my mother’s when she was younger. Would you believe she used to be a terrific rider? You’d never guess now, seeing her, that she won a whole load of trophies. She had her own horse. Then she got married and had me. She gave me riding lessons for as long as she could afford it. I bet she’s still better on a horse than me, even now. Here, look.” She opened a drawer in the table underneath the goldfish and pulled out a photo album. She opened it and put it in Juan’s lap.

In it, were snapshots of a woman dressed in impeccable riding togs and sitting astride a large gray hunter. They were jumping over a huge fence in one photo, and a couple of newspaper clippings, faded and well-worn, were taped to the opposite page. He turned the page and saw the same woman receiving prizes, or jumping fences, always with the same horse. He tried to see the resemblance to Rennie, but couldn’t. The woman was a pale blonde with an austere expression on her angular face. She had wonderful style though, Juan could see that. She also looked familiar. He felt he should know her.

“Does she ride anymore?” he asked.

“No, not since I was born.” Rennie sounded forlorn. “She had a problem when I was born, something to do with her back. She could never ride again.” She stopped talking and looked away. Juan saw she was fighting tears, so he quickly changed the subject.

“Shall we go?” He wondered what Andre was going to say. He hoped he hadn’t found anyone else. Suddenly, it seemed important to keep Rennie close to him. He wondered if he was developing a crush on her.

* * * *

Rennie was silent during the drive. Actually, she was petrified. She wondered what had prompted her to ask for the job. She’d never groomed before. She could ride, but she’d never taken care of more than one horse at a time. Juan had said she’d have six to care for.

Furthermore, how was she going to tell her mother, or on a more practical note, get to work? She’d have to take the bus, then walk through the club.

She was staggered by the size of it. They went through the front gate and Rennie goggled at all the mansions lined up along the drive. There were tennis courts and swimming pools everywhere. There were real gardens here, with rose bushes, hibiscus and tons of other flowering plants that Rennie couldn’t put a name to. She’d seen mansions before, of course. Palm Beach had its Worth Avenue and the coast was one of the wealthiest in the world, but the polo club impressed Rennie. Everything impressed her. Arched bridges crossed the dark water of the canal. The landscaped gardens were beautifully groomed, as were the polo fields. There were huge expanses of perfectly mowed lawn with gleaming red sideboards running down their entire lengths. Rennie couldn’t believe it.

Tucked into an endless orange grove, the barn was beautiful but unassuming. It was set amid four square paddocks and a tree-lined drive led to the parking lot in the back. Two other cars were parked there, as well as a pickup truck and a converted cattle trailer built to carry twelve horses to and from matches.

Two apartments tagged on either end of the stables, and the stables themselves consisted of a double line of stalls built along a corridor in the middle of the barn. Twelve ponies faced out toward the orange groves, and twelve faced the parking lot and driveway. Each stall had a fan in it, and automatic watering troughs.

Rennie found her throat was so dry she couldn’t speak. She trailed after Juan as he went toward the east side of the barn and hollered for Andre.

A curly head of black hair appeared. Is this Andre? He had a friendly face under all those black curls, decided Rennie. His nose had obviously been broken before and had been set crookedly. He also had a wicked-looking scar that cut his bottom lip into two pieces.

“Andre, here’s your new groom,” announced Juan in Spanish as soon as he’d opened the door.

Andre looked surprised. “But I wanted a man this time, not a woman. Where did you find her?”

“On the side of the road,” joked Juan. “Why don’t you give her a try and if she doesn’t work out, we’ll look for someone else. The advantage is that she’s American. No problems with green cards or work permits.”

Andre shrugged. “Okay by me. What’s your name?” he asked her.

“Rennie. Rennie Piccabéa. “

“Piccabéa, Piccabéa. The name sounds familiar,” said Andre, wrinkling his forehead.

Juan thought so, too, and it suddenly dawned on him. “Your mother is Marilyn Piccabéa?” he asked, incredulous.

Rennie said, “Yes, she was. She is, I mean.” She was surprised they’d recognized her mother’s name. Nobody ever had before.

Juan nodded. “Of course. I didn’t recognize her from those old photos. She was on the Olympic team. Those little trophies, they were silver medals. Her horse was the Sergeant, wasn’t he?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“You could’ve told me,” he said crossly.

Rennie flushed. “Sorry, I’m not used to talking about it. We never do. Anyway, it was a long time ago.”

“How old are you?” Juan asked.

“Twenty-one.”

Juan tapped his chin pensively. “I don’t remember her, but my father was on the English jumping team and he used to talk about your mother when he spoke about the Olympics. He never knew why she stopped…”

Rennie tightened her lips. “It was because of me,” she reminded him. “I was a breech birth and it hurt my mother’s back.”

Juan noticed the set of her mouth. “Sorry.”

Rennie sighed. “It’s okay. She married her trainer right after the Olympics. Then she had me.”

“Your father was her trainer?” asked Andre. He sounded amused.

“For a while. Then he had an accident and died. My mother says we’re cursed,” she added, looking suddenly worried.

“Poor kid!” said Andre. “Well, I don’t believe in curses. You can start tomorrow at five a.m. I’ll show you around now and tell you what’s to be done. The horses are all pretty good, except Pinto, the paint pony. He’s green.” He turned and pointed to a truck. “That’s the grooms’ pickup, you can use that. You have a driver’s license, don’t you?”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter